On February 14, 2023 we announced our Rebuttal Update Project. This included an ask for feedback about the added "At a glance" section in the updated basic rebuttal versions. This weekly blog post series highlights this new section of one of the updated basic rebuttal versions and serves as a "bump" for our ask. This week features "Was Greenland really green in the past?". More will follow in the upcoming weeks. Please follow the Further Reading link at the bottom to read the full rebuttal and to join the discussion in the comment thread there.

At a glance

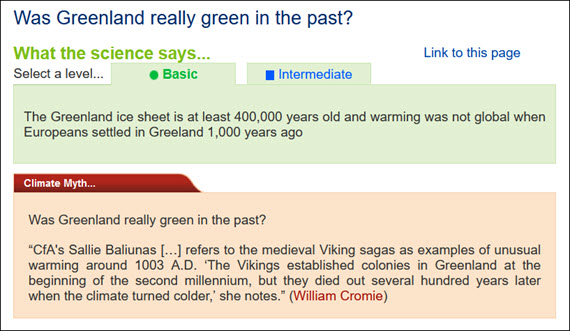

The past 2024 years - i.e. everything AD - are referred to by archaeologists as the Common Era (CE). Decades ago, long before the refinements and data-coverage of modern science, the CE was divided into a series of climate epochs. Among these were the 'Mediaeval Warm Period' (MWP), from around 800-1200 CE and the 'Little Ice-Age', from 1200-1850 CE.

Each of these epochs has the origin of its name in older paleoclimatic evidence from the Northern Hemisphere and particularly Europe. But things have moved on. We now know that unlike modern global warming, the MWP was regional in its nature. A particularly warm region was the Northern Atlantic, including southern Greenland.

Icelandic sagas tell how, in 982 CE, Erik the Red was sentenced to exile from Iceland for three years. He had been involved in an escalated dispute with a neighbour that had culminated in several deaths. With a band of fellow Vikings, he set sail towards Greenland. Erik's party landed and settled near the mouth of Tunulliarfik Fjord, which has the modern Innuit settlement of Narsarsuaq at its head. This part of Greenland is a largely ice-free enclave today, situated in the SW part of the island, some 200 km from its southern tip. Legend tells how Erik came up with the name, 'Greenland', in order to attract further settlers. Apparently the ploy worked.

With hundreds of settlers arriving in the SW of Greenland, a mixed economy developed. It was based on combined pastoral farming, hunting and fishing. Livestock were kept mostly for milk, cheese and butter. Meat instead came mostly from hunting, both locally and in seasonal expeditions further north. These longer forays visited areas in which walrus, narwhal and polar bears were abundant. Hides and ivory became export commodities, allowing maritime trade with the rest of Europe, in return for iron, timber and other essentials.

A few centuries into this colonisation, the regional climate deteriorated. Ice-sheets readvanced. Recent research has also shown that sea-levels rose, too. It may seem counter-intuitive, but when ice sheets grow, nearby coasts often drown. Two things work together to cause this: the larger gravitational pull of all the extra ice on the sea surface and the subsidence of Earth's crust due to the added weight of that ice. One recent study has suggested over 200 square kilometres of coastal land - where the settlers would have had many of their farms - were lost. Geophysics has detected remains of some of the settlements, now beneath the waves.

Progressive sea-level rise, likely in tandem with social and environmental factors such as famines, epidemics and harsher weather, took its toll. The Inuit, who had arrived in around 1200 CE, remained in Greenland through the severe cold of the Little Ice Age but by around 1500 CE, the Vikings had vanished for good. Climate change drove them out.

That's what happened to the Vikings. But regional and global climate change are different things. Regional historic change has little bearing on the global events that are happening right now.

Please use& this form to provide feedback about this new "At a glance" section. Read a more technical version below or dig deeper via the tabs above!

Click for Further details

In case you'd like to explore more of our recently updated rebuttals, here are the links to all of them:

&

If you think that projects like these rebuttal updates are a good idea, please visit our support page to contribute!

Comments